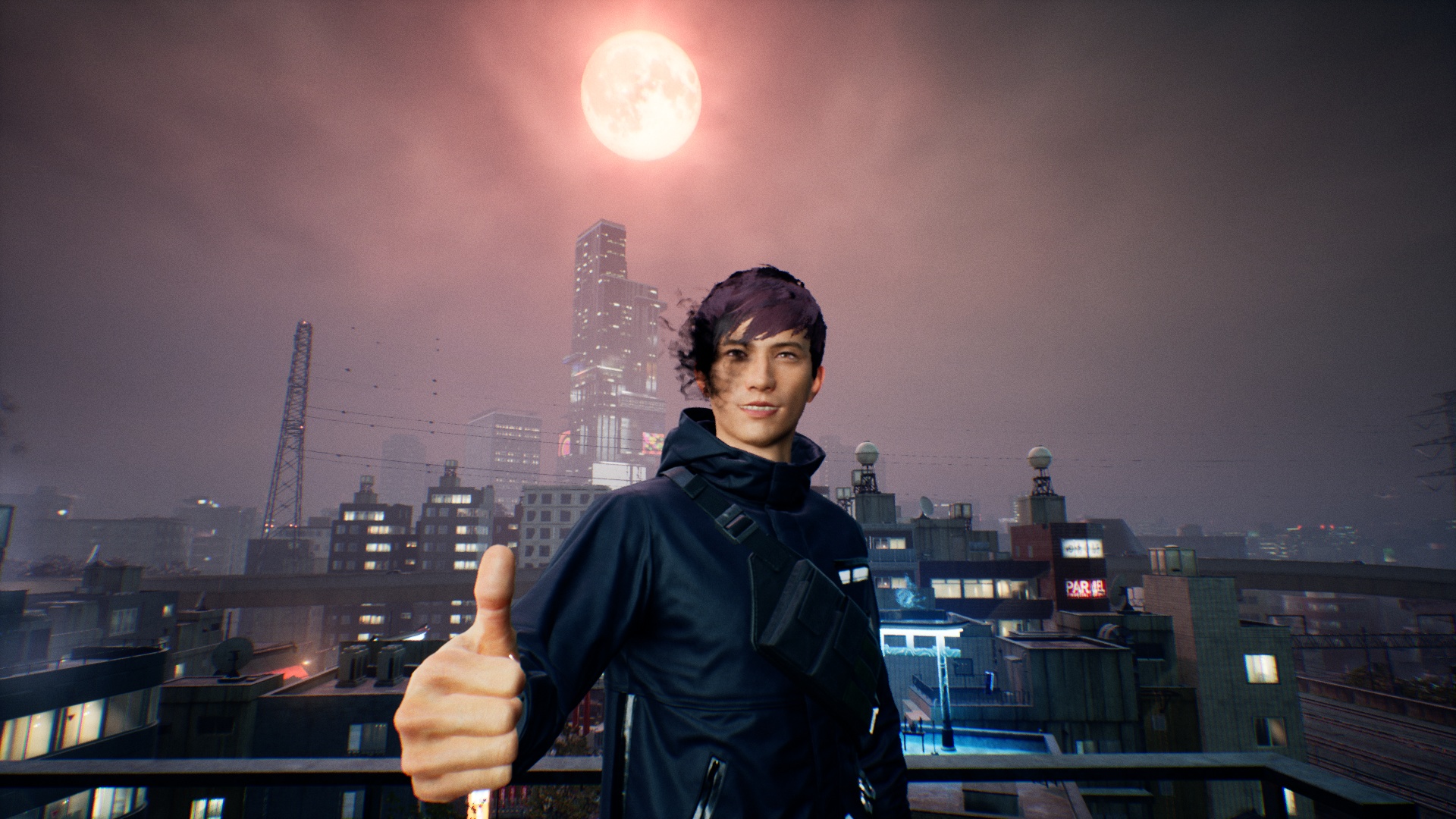

The magic shooter from Tango Gameworks shows that a fancy open world and a nice story can fail because of average gameplay.

The story of Ghostwire: Tokyo is actually clichéd: Chief villain Hannya covers Tokyo with a mysterious mist that turns all humans into ghosts and in whose wake numerous demons (Yokai) make the streets unsafe. Only our hero Akito is strangely spared, but is instead possessed by a spirit called KK, with whom he henceforth shares his body.

KK gives Akito, and thus us, magical fighting abilities, which we can put to good use. For it is not only a matter of driving away the “visitors” and stopping Hannya. We also have to save Akito’s sister Mari. She was kidnapped from the hospital by Hannya because he needs her for a dark ritual. Hannya wants to tear down the border to the world of the dead to create a new ‘paradise’ – a paradise, of course, that is only desirable in Hannya’s own world view.

Table of Contents

Anchored in myths

So far, the story is nothing special. There are three reasons why it still managed to captivate us in front of the screen:

Reason number 1

The is story is well embedded in Japanese mythology. This starts at the beginning, where we watch ghosts on their way to Hannya, walking down the street to sustained music. This is seemingly inspired by the Hyakki Yagyo, the nightly parade of one hundred yokai that takes place mainly on summer nights and during Obon. Obon is a Buddhist festival when the spirits of the dead visit their living relatives. It is celebrated in Japan in August, and when we look at a calendar in offices of the game, we see that it is indeed August.

The Yokai in the game also feed off traditional sources: We encounter two-tailed cats (Nekomata) who act as shopkeepers. We fight in a boss fight against a likewise cat-like, but not at all cuddly Bakeneko. In a side quest we encounter a frog-like kappa; in another side quest we take care of a zashiki warashi, a child-like spirit that is considered a good luck charm for houses and over which a landlord and his tenant therefore fight.

Other enemies come from more recent pop culture: we have to watch out for the Kuchisake Onna – a woman with a face mask and giant scissors who became an urban legend in Japan in the 1970s. In the legend, Kuchisake Onna asks unsuspecting passers-by if she is beautiful. If you agree, intimidated, she pulls off her mask, asks: “now too?” and her creepily incised mouth is probably the last thing you see of her.

Except just now, we’re playing Ghostwire: Tokyo, where our fighting skills save our necks. An interesting commentary on society is the rain runners picking up Karoshi, death by overwork (heart attack, stroke). As zombie-like as crunching employees in game companies might feel, the rain runners creep up on us. In grey suits, umbrella in hand.

Reason number 2

The main characters are only characterised with a few brushstrokes – or they are immediately behind masks reminiscent of No-Theatre – but these are enough to understand their motivations and attitudes. The very good voice-over in German, English and Japanese does its part. Especially Akito’s affection for his sister, which he has never been able to express properly, as well as Hannya’s pain, the cause of which we learn about in the course of the story, are comprehensible (although Hannya is of course still just crazy).

In addition, Akito and Hannya’s experiences mirror each other, which has a certain narrative elegance. KK and his fellow Ghostbuster Rinko remain somewhat pale; in particular, the cause of their enmity remains open (though you can play the free visual novel Ghostwire: Tokyo – Prelude to learn more about both).

Cause number 3

Thirdly and finally, we really enjoyed the staging of some key moments, surreal level sections and the final thirty minutes or so. The resolution is emotional, but doesn’t drift into the cheesy – which is again due to the fact that, with a few exceptions, we only see ghostly shadows of the past instead of real people.

And maybe it was the late hour (we finished the story at exactly 3:23 a.m.), or the current world situation, but the end of the game felt like a cathartic experience that somehow released not only Akito, his sister and KK, but also us as players.

Atmospheric, beautiful, dead: the open world

Despite the open world, the main story, which is about 14 to 16 hours long, can be followed in a very linear fashion. Your companion KK always tells us what needs to be done and that it is urgent. Since there are nevertheless side quests and collecting tasks, Ghostwire: Tokyo has an old open-world problem: according to the main story, a great doom is looming, but it kindly waits until we find time for it.

So it’s easy to lose sight of the story while we play side quests or indulge our collecting instincts. We therefore concentrated mainly on the main story from chapter 3 onwards and recommend you do the same. The game warns you in good time towards the end when there is no turning back, if you still want to complete all the side quests.

In the first few minutes of the game and for the first few hours, the virtual Tokyo is very atmospheric. Although there are no people at all, only the Yokai and the motionless ghosts, sound and a great graphic realisation provide the believable impression of moving through a real, albeit empty, city.

Even if we only know Tokyo from films, series or YouTube videos, familiar places are easily recognisable. First and foremost, the intersection in front of Shibuya station, the station itself and the adjacent department stores. In contrast, we walk through narrow alleys with small shops and visit shrines whose sacred area is separated from the everyday world by gates called Toori.

The Unreal engine conjures up beautiful light and mirror effects in the night in either 30 or 60 FPS. Even at the lowest texture setting, everything is very sharp, texts are perfectly recognisable and we regretted several times not knowing Japanese, because with it we can get much more of the city. But even so, we had the feeling for a long time that we were seeing a very detailed replica of Shibuya. The big streets, the intersections, the skyscrapers, the motorway and the railway line – it all fits. How great it would be to see that enlivened by people!

But because people are missing, cracks in the shiny façade become visible in the long run. Because without inhabitants, we inevitably concentrate on the scenery. And then we notice the same cars and motor scooters; the same clothes and bags lying around (abandoned by their owners who became ghosts through the fog); and the same dogs roaming around, happy when we give them food.

Businesses and window displays meet us identically in different places in the city, the numerous buses all have the same destination, and even the soundscape repeats itself. If people were moving through the streets and alleyways, all this would be less noticeable.

The story doesn’t need an open world

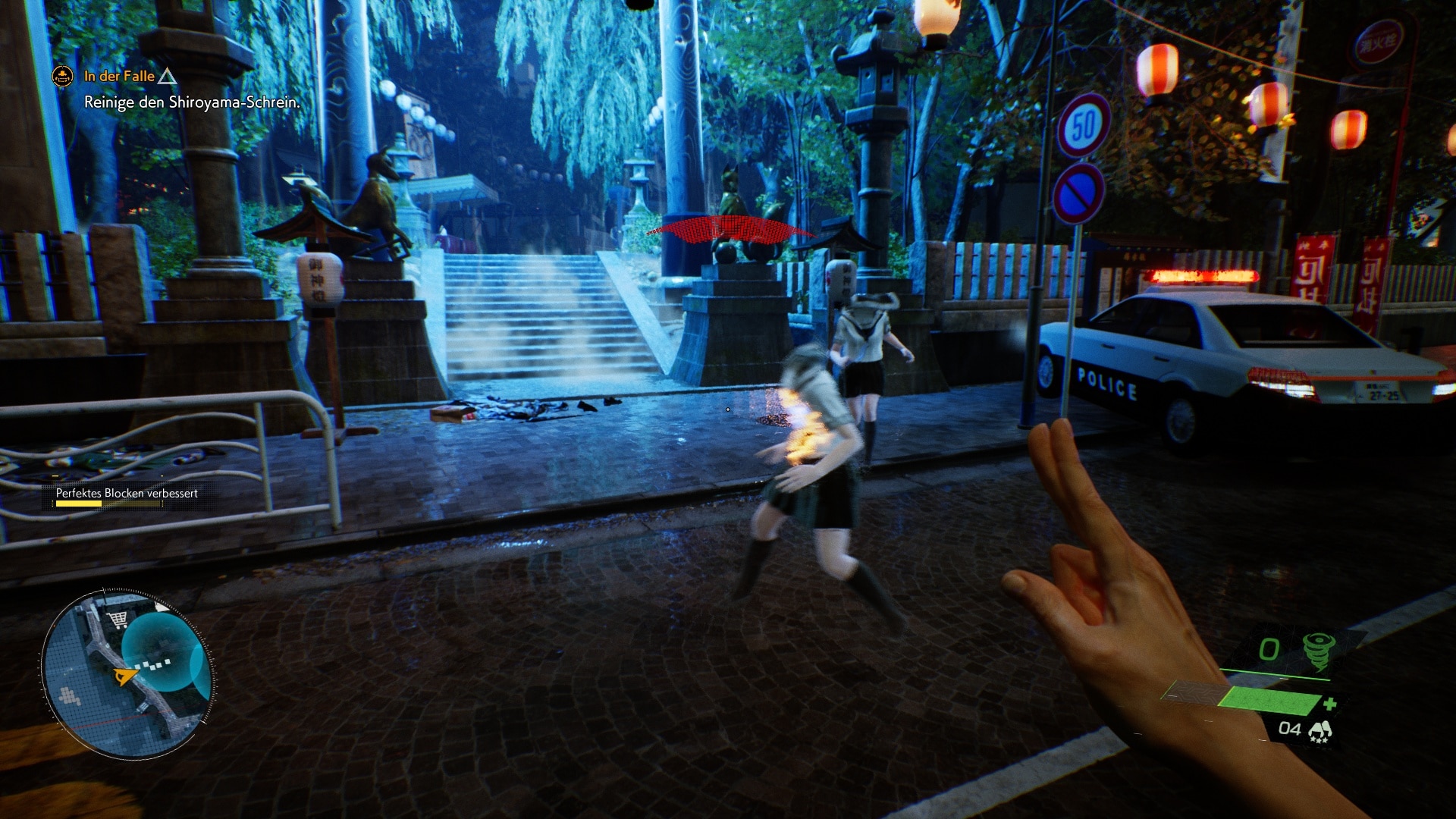

In terms of gameplay, the open world doesn’t really fit into the story either. Initially, the walkable area is limited by deadly fog, but the more torii (the aforementioned access gates to Shinto shrines) we clear, the more quarters become accessible.

Of course, the torii are guarded by yokai; major battles occur at particularly important ones. Some torii are on the roofs of skyscrapers, which we reach either with the help of flying yokai, or quite banally via stairs and lift. From above, we have a good overview and can reach some places faster by hovering (but fortunately we can’t crash fatally).

The main story only takes place in one part of the map – torii by torii, quarter by quarter, we work our way towards Tokyo Tower, where the big showdown begins. Unfortunately, this also means that the open world is not necessary for the story.

It serves more for collecting ghosts, which we exchange for experience points in phone boxes, and as a setting for (quite interesting) side quests, which deepen the background of the ghost world and Yokai myths. In terms of gameplay, the world is otherwise only significant when it comes to creatively avoiding monsters or fighting them in a certain way.

Squishy battles

The fights take place in a ‘magical’ way. We fight the opponents with the three elements wind, water and fire. Akito fires the attacks with gestures of his hands. In terms of gameplay, this is limited to selecting the element and pressing the fire button. Ghostwire: Tokyo thus plays like a shooter, but without a visible weapon to provide feedback.

The fighting gestures are said to be inspired by traditional kuji-kiri. But unfortunately the hand animation lacks a certain body tension that we imagine for controlled fighting gestures. That’s why the attacks feel strangely lax. We like the fire attacks best (single or charged up by prolonged pressing for a big explosion).

Movement in combat could also be more precise. Ghostwire: Tokyo is a console game, the manufacturer recommends a controller for control. A large crosshair with aiming aid and switchable lock-on ensure that we cannot miss slow or standing enemies. Fast enemies are less easy to aim at, but this works better with the mouse and keyboard.

But even there we move relatively slowly and due to the lack of a dodge function we sometimes run away a bit headless. This makes the fights feel less controlled than they could be. Various talismans help to master the greatest chaos: Some lucky charms can paralyse opponents for a short time, others weaken them.

Better with bow and arrow

Distinctly more satisfying are the finishers: when an enemy has taken enough damage, its “core” is exposed (probably the manifestation of its soul) and we can pull this out by holding down a button for several seconds. Here we actually have the feeling of power and control, because this act is animated with a kind of energetic rope, which we slowly wind up and thus tear out the core. The rope is the connection of ‘our’ hands to the opponent, which is missing in all other attacks.

Also nice: the fight with bow and arrow. We get this alternative weapon early in the game, where it is not yet that important. Later, it helps us take out distant slow enemies like a sniper from rooftops or hidden behind a car. This feels good and controlled. However, we can keep the bow drawn endlessly; Akito’s arm never seems to weaken, start shaking or falter.

The bow takes on special significance when we are temporarily without KK. Because without our spiritual companion we have no magical abilities and the bow is the only method to keep enemies at bay. This almost has something of a survival and stealth interlude, and these moments are also the ones in which we really feel vulnerable. They give an impression of how Ghostwire: Tokyo could have been if the shooter mechanics had been better, or at least if the endless supply of ammunition had been severely limited.

Unmotivated skill system

By defeating enemies, trading spirits and completing quests, we gain experience points and level up. In addition to increased health, we also receive skill points that we can use in three talent trees. However, special builds like in a role-playing game are not possible. We also don’t get new abilities; existing ones only become stronger. For example, we can hover longer, our fire attacks cause more explosion damage, the core of enemies is exposed longer for pulling out, or we can carry more arrows for the bow.

By the end of the main story, we had activated just under 70 per cent of all unlockable skills; had we gained even more experience in side quests, we probably would have unlocked everything by the end. It doesn’t feel like a significant decision to invest in a skill. In principle, the game could automatically improve the respective traits every time you level up, without losing much.

Editor’s conclusion

When the credits of Ghostwire: Tokyo flickered across the screen of my PC shortly before half past three in the morning, I was very tired because of the late hour, but felt strangely liberated. I had just experienced the end of the main story, which entertained me throughout and even touched me a lot at the end. I suffered with the characters and shared Akito’s catharsis at the end. I was satisfied with the outcome of the story, which began hours earlier with a procession of Yokai across Tokyo’s famous Shibuya intersection and immediately sucked me in with the atmosphere of a neon-glittering ghost town.

Therefore, I forgive the game’s weaknesses, especially the repetitive structure (search for and clean torii, collect spirits and exchange them for experience, complete sections in buildings, occasionally interrupted by cutscenes and boss fights), the unnecessary skill tree as well as the spongy combat system that conveys little of the physicality that one should associate with the hand gestures shown.

It’s a shame that the open world has little relevance to the main story. If I want, I can follow the story stringently from start to finish (KK always tells us where to go) and ignore the rest of the map. More tubular levels would have been enough. But at least the world is graphically well realised and the side quests deepen the mythological background. Ghostwire: Tokyo is a journey into a part of Japanese culture that is less familiar to us. If you are interested in this, you are welcome to add a few points to my rating in spirit.